|

Notes l Bibliography l Download Issue 1

|

|

An illustration from Collier's Weekly, February, 1904 |

In December 1893, "The Final Problem" appeared in The Strand Magazine, signaling the start of eight long years without a new Holmes story. As they read "The Final Problem," readers were outraged to discover that their beloved character had apparently died while struggling with his nemesis Moriarty at the edge of a cliff. Arthur Conan Doyle had tired of his most popular creation, and was occupied with his first wife, who was gravely ill with tuberculosis. The public didn't have much sympathy. Over 20,000 people cancelled their subscriptions to The Strand Magazine, whose staff referred to Holmes's death as "the dreadful event."

In 1901, The Strand ran a new Holmes serial, the nine-part Hound of the Baskervilles. Conan Doyle was not convinced to truly resurrect Holmes until two years later. In October 1903, "The Empty House" marked the definitive return of the master detective.

Events portrayed in "The Final Problem" take place in 1891, while "The Empty House" takes place only three years later, in 1894. Wisely, Conan Doyle decided to keep Holmes and Watson in the Victorian age.

...the Honourable Ronald Adair.... (1)

Children of a peer, male or female, would have "The Honourable" placed before their names.

...the third of last month. (1)

Watson is only allowed to reveal Holmes's "resurrection" to the public after Holmes retires to the Sussex Downs in 1903 to keep bees and write about beekeeping, enjoying an "occasional weekend visit" from Watson (see "The Lion's Mane," 1926).

|

|

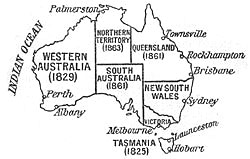

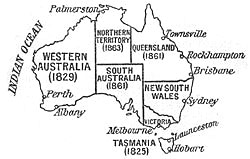

A map of the six Australian Colonies in 1863 (the Northern Territory was under the administration of South Australia), from Ernest Scott, A Short History of Australia (Melbourne, Oxford UP: 1916) |

...Governor of one of the Australian colonies. (1)

Captain Cook took possession of Eastern Australia for England in 1770. A few years later, with the loss of the American colonies, British interest in colonizing Australia increased. Penal colonies were established, and eventually freed convicts were settled as sheep farmers in New South Wales. In 1901, the six colonies, Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia, and Western Australia, formed a British Commonwealth, with a Prime Minister and a two-house legislative body.

From his childhood on, Conan Doyle enjoyed stories about "exotic" locales (all colonized at one time by the British), such as India, North America, Africa, and Australia. His very first published story, "The Mystery of the Sasassa Valley" (1879), was about South African miners. As a young man, Conan Doyle signed on as a ship's doctor and visited Antarctica and Africa. He did not visit Australia until 1920, during a lecture tour on spiritualism. This did not prevent him from mentioning Australia or creating characters with Australian backgrounds in such stories as "The Boscomb Valley Mystery" (1891), The Adventure of the Gloria Scott" (1893), and "The Adventure of the Abbey Grange" (1904).

|

|

A row of mansions along Park Lane, from George Clinch, Mayfair and Belgravia: Being an Historical Account of the Parish of St. George, Hanover Square (London: Truslove & Shirley, 1892) |

...were living together at 427, Park Lane. (1)

Park Lane lies in Mayfair, a small, fashionable district in the City of Westminster. The street runs along the eastern edge of Hyde Park, between Oxford Street on the north and Green Park on the south. Today, many of the 17th- and 18th-century mansions that line Park Lane have been converted into commercial enterprises, such as restaurants and fine shops, while others have been replaced by upscale hotels.

...Miss Edith Woodley, of Carstairs.... (2)

Carstairs is an ancient village in southern Scotland.

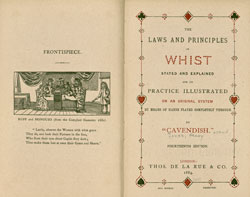

...the Baldwin, the Cavendish, and the Bagatelle card clubs. (2)

Gaming clubs in the West End of London were popular in the 1890's among gentlemen whose fortunes allowed them to risk some cash. In London Clubs, Their History and Treasures (London: Chatto & Windus, 1911), Ralph Nevill says that, at the Baldwin Club, the "stakes are very small," while, at the notorious Crockford, things were different. "Here the wily proprietor neglected nothing to attract men of fashion of that day, most of whose money eventually drifted into his pockets" (189).

|

|

Crockford's gambling club in 1828, from Ralph Nevill, London Clubs, Their History and Treasures (London: Chatto & Windus, 1911) |

|

| The frontispiece from Nevill's book, showing the St. James Club |

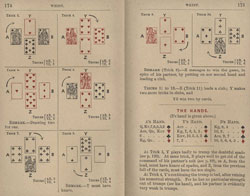

...he had played a rubber of whist.... (2)

Whist is a trick-taking card game–a predecessor of bridge. It enjoyed enormous popularity in the 18th and 19th centuries. A rubber is a full round, usually two games out of three.

|

|

"Cavendish's" popular book on whist explained the game in detail, including sample plays. Henry Jones (pseud. Cavendish), The Laws and Principals of Whist Stated and Explained. 14th ed. (London: Thomas de la Rue & Co., 1884) frontispiece and title page. Below is a sample hand of whist from Cavendish's book. |

|

...the front room on the second floor.... (2)

In Britain, the second floor is two flights up; Americans would call it the third floor.

...by an expanding revolver bullet.... (2)

Also known as a "dum-dum" bullet for Dum Dum, the town in India where it was manufactured, this expanding bullet was developed by the British in the 1890s for use in India. The exposed soft "nose" of the bullet (covered by a hard metal jacket in conventional bullets) expanded upon impact, thus causing much more tissue damage than a normal bullet. The use of dum-dums during warfare was banned by the Hague Convention in 1899.

...the Oxford Street end of Park Lane. (2)

In other words, the northern end.

...I observed the title of one of them, "The Origin of Tree Worship," and it struck me that the fellow must be some poor bibliophile.... (3)

Could Watson mean J. H. Philpot's The Sacred Tree, or the Tree in Religion and Myth, (London: Macmillan, 1897)? Unfortunately, it was published three years after The Empty House is supposed to take place, but not after it was written.

The point here is to reinforce the image of the man with the dark glasses as a somewhat obsessed bibliophile (rare-book collector).

|

To return home from Park Lane, Watson has a pleasant walk through Hyde Park and Kensington Gardens. Church Street, where the bookseller has his shop, can be seen between the L's in "Hill" at left.

|

...retraced my steps to Kensington. (3)

In "The Final Problem," Watson apparently lived near Mortimer Street, but now has moved to Kensington. These two locations, and Baker Street, are all on the West End, but Kensington is the furthest west, almost at the outskirts of London.

|

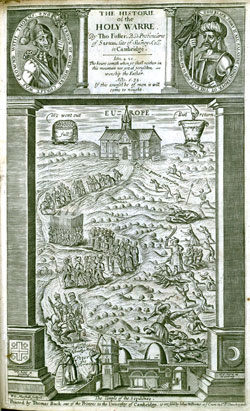

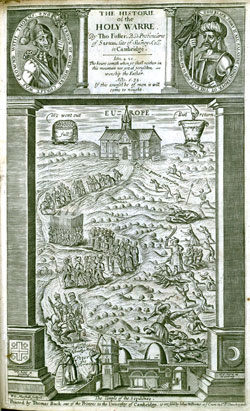

The title page and frontispiece of Stanford University's copy of Thomas Fuller's The Holy Warre

|

|

"...here's 'British Birds,' and 'Catullus,' and 'The Holy War'–a bargain, every one of them. With five volumes, you could just fill that gap on that second shelf." (4)

'British Birds' might be Thomas Bewick's A History of British Birds, 2 vols., issued in 1821 and reissued in 1847. The title page and an illustration from Bewick's book can be seen in last year's notes.

Catullus (84-54 B.C.) was a Roman poet.

There are three books called The Holy War: an allegory by John Bunyan, and histories of the Crusades by Thomas Mills and Thomas Fuller. It is impossible to know which one the bookseller means. John Bunyan, A true relation of the holy war, made by King Shaddai upon Diabolus, for the regaining of the metropolis of the world: or, The losing and taking again of the town of Mansoul (London, 1684); Thomas Mills, The history of the holy war: began anno 1095, by the Christian princes of Europe against the Turks, for the recovery of the Holy Land, and continued to the year 1294 (London, 1685); Thomas Fuller, The History of the Holy Warre, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, 1640). Perhaps the fourth volume the bookseller carried was The Origin of Tree Worship, the same book he had with him before. We have no hint what the fifth book was, but that has not prevented Sherlockians from speculating about it.

"I had no idea that you would be so affected." (4)

Holmes often seems to enjoy surprising others, although he does not relish surprises himself. At the end of "The Naval Treaty" (1892), he hides the recovered document in a covered dish and asks Watson's friend Phelps, from whose desk the treaty had disappeared, to serve him some food. The poor man has a bad reaction to this trick.

"Phelps raised the cover, and as he did so he uttered a scream and sat there with a face as white as the plate upon which he looked. Across the center of it was lying a little cylinder of blue-grey paper. He caught it up, devoured it with his eyes, and then danced madly around the room, pressing it to his bosom and shrieking madly in his delight. Then he fell back into an arm-chair, so limp and exhausted with his own emotions that we had to pour brandy down his throat to keep him from fainting."

"Sit down, and tell me how you came alive out of that dreadful chasm." (5)

See our archived Sherlock Holmes adventure "The Final Problem."

"I have some knowledge, however, of baritsu, or the Japanese system of wrestling...." (5)

"Baritsu" is most likely a mistake for "bartitsu," a martial art popularized by an Englishman named E.W. Barton-Wright (1860-1951). Bartitsu is a combination of the Japanese self-defense system, jujitsu, combined with some wresting and boxing techniques. Bartitsu and jujitsu are, like many Asian martial arts, based on the principle of using the opponent's strength against him. The Empty House was published four years after Baron-Wright introduced his system, but was supposed to take place eight years before. In his article, "The New Art of Self-Defense: How a Man May Defend Himself against every Form of Attack" (Pearson's Magazine, March 1899), Barton-Wright gives many useful techniques, with photos, for such tasks as defending yourself against someone with a knife, ejecting a troublesome person from a room, and preventing someone from striking you in the face. See a reprint of Barton-Wright's article on-line in The Journal of Manly Arts, Nov. 2002.

"I knew that Moriarty was not the only man who had sworn my death. There were at least three others whose desire for vengeance upon me would only be increased by the death of their leader." (5)

Perhaps Holmes has forgotten, but, in "The Final Problem," he told Watson that all of Moriarty's confederates would be caught by the plan Holmes had set in motion before his departure from England. "They have secured the whole gang with the exception of him. He has given them the slip," Holmes tells Watson after reading a telegram from the London police.

"I took to my heels, did ten miles over the mountains in the darkness, and a week later I found myself in Florence, with the certainty that no one in the world knew what had become of me." (6)

Having sewn up matters tightly in "The Final Problem," with hopes that Holmes would never be resurrected, Conan Doyle now finds himself in something of a pickle. The story he concocts to explain Holmes's absence ships water at several points. If Moriarty's rock-tossing confederate knew that Holmes was alive, why didn't the whole London criminal world soon know? How could Holmes reach Florence from the Alps without being found? Why didn't Moriarty's sharp-shooting confederate shoot Holmes, instead of flinging rocks at him?

"Several times during the last three years I have taken up my pen to write to you, but always I feared lest your affectionate regard for me should tempt you to some indiscretion which would betray my secret." (6)

All justifications aside, Holmes's failure to tell Watson of his whereabouts is surely too cruel an act to be forgiven as quickly as it is by Watson.

|

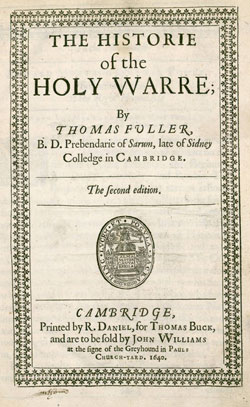

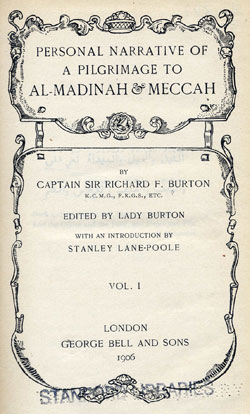

The frontispiece from volume one of Burton's book, Personal Narrative of a Pilgrimage to al-Madinah and Meccah (3 volumes, 1855-6; 2nd ed. 1906)

|

|

| Photo of the Tashi Lama's palace in Shigatse (1907) from Sven Hedin, Trans-Himalaya: Discoveries and Adventures in Tibet, 3 vols. (Macmillan: London, 1910) |

"I traveled for two years in Tibet, therefore, and amused myself by visiting Lhassa [sic], and spending some days with the head Llama [sic]. You may have read of the remarkable explorations of a Norwegian named Sigerson, but I am sure that it never occurred to you that you were receiving news of your friend. I then passed through Persia, looked in at Mecca, and paid a short but interesting visit to the Khalifa at Khartoum, the results of which I have communicated to the Foreign Office. Returning to France, I spent some months in a research into the coal-tar derivatives, which I conducted in a laboratory at Montpelier [sic], in the south of France." (6)

Holmes's exploits over the three years of his disappearance touch upon two exotic locals where Englishmen could not easily enter.

Foreigners had been banned from Tibet since 1792. During the 19th century, Britain was trying to establish trading agreements with Tibet by negotiating with China, which claimed sovereignty over Tibet. Tibet rejected several treaties in succession, and was instead strengthening its ties with Russia. This situation reached a crisis in 1904, when Britain invaded Tibet to protect what it saw as its economic interests. For an Englishman to travel in Tibet during that period of diplomatic estrangement would have required great facility in disguise, which, of course, Holmes possessed.

Neither the Dalai Lama (who was a teenager when Holmes disappeared), nor any other lama, would have appreciated being referred to as a "llama," a pack animal from South America. Conan Doyle's mistake went uncorrected in many early editions. Conan Doyle's cavalier reference reveals his desire to gloss over Holmes's adventures during the hiatus and get on with the story.

To fill in Holmes's lost time, Conan Doyle drew on sources that were common knowledge for Victorian readers. Holmes's alter-ego, Sigerson, resembles other well-known (mostly self-promoting) 19th-century European explorers who visited (or claimed to visit) exotic locals. Henry Morton Stanley's (1841-1904) voyage to Africa in search of Henry Livingston (who himself was searching for the source of the Nile) made him world famous. Edward John Trelawny (1792-1881), a friend of English poets Byron and Shelley, made a sensation with his Adventures of a Younger Son (1831), a volume describing highly embroidered exploits in India and elsewhere. Richard F. Burton (1821-1890) traveled in disguise to the Middle East, where no Englishman would have been welcome, converted to Islam, and made a pilgrimage to Mecca. Swedish explorer Sven Hedin (1865-1952) published accounts of his travels through the Middle East and central Asia. At the time "The Empty House" was published, Hedin had just returned from an expedition to Tibet. Unlike Holmes, Hedin was denied entrance to the holy city of Lhasa. During his third expedition (1906-8), Hedin received Tibetan permission to stay in the holy city of Shigatse (against the wishes of the British government) and had an audience with the Tashi Lama.

The Khalifa had abandoned Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, in 1885, after its capture by followers of Muhammad Ahmad, who led a rebellion against British rule of the Sudan. In 1899, Ahmad's successor, Khalifa 'Adb Allah (1846-1899), was killed when the British retook Egypt and the Sudan. (For a tongue-in-cheek article detailing Holmes's service to the Crown in Khartoum, see Margaret Nydell, "Sherlock Holmes in Khartoum" (Baker Street Journal, Vol. 51, No. 3) 13pp.)

The Foreign Office, today known as the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, is the arm of government responsible for England's contacts with other countries in every sense, from diplomacy to spying.

It is not clear what aspect of "coal-tar derivatives" Holmes might have been studying. Coal-tar derivatives are by-products of the transformation, under high heat, of bituminous coal to coke. The resulting by-products are further refined, and used in products as diverse as cosmetics, medicines, and explosives.

"Montpelier" is a misspelling for Montpellier, a city in southern France, the location of a famous university.

In some manner he had learned of my own sad bereavement.... (6)

Watson apparently refers to the death of his wife, the former Mary Morstan. He never reveals the details or the cause of her death.

|

|

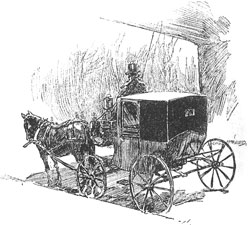

A drawing of a hansom cab, from "The Final Problem," McClure's Magazine (vol. II, no. 1, January 1894), illustrated by Harry Edwards

|

...I found myself seated beside him in a hansom.... (7)

A hansom was a horse-drawn cab that usually seated two or four people.

I had imagined that we were bound for Baker Street, but Holmes stopped the cab at the corner of Cavendish Square. [...] Holmes's knowledge of the byways of London was extraordinary, and on this occasion he passed rapidly, and with an assured step through a network of mews and stables the very existence of which I had never known. (7)

"Mews" are back alleys where stables open behind houses or businesses, a good resource for someone who wanted to cover a lot of ground without being seen. They were often odiferous places where stablehands and workmen gathered. They were not generally frequented by the upper classes. Although some mews–and their passage through the stables to the carriage entrance at the front of the building–probably aren't shown, the map below gives a general idea of Holmes's possible routes from Cavendish Square to Manchester Street, Blandford Street, and on to Baker Street, and how he could have maximized travel through mews and minimized exposure on the open streets.

|

On this map from Baedeker's 1911 London and its Environs, "Ms." is an abbreviation for "Mews." From Cavendish Square, right, to Baker Street, left, Holmes has several routes to choose from. |

"We are in Camden House, which stands opposite to our old quarters." (8)

Sherlockians have argued over the exact location of 221B Baker Street. During Conan Doyle's time there was no 221B until Baker Street was extended north into Upper Baker Street and York Place.

"...the starting-point of so many of our little adventures?" (8)

As usual, Holmes pretends to take a dim view of Watson's tales, all the while enjoying the notoriety they bring him.

"I trust that age doth not wither nor custom stale my infinite variety," said he, and I recognized in his voice the joy and pride which the artist takes in his own creation. (8)

Holmes paraphrases Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra, Act II, scene 2: "Age cannot wither her, nor custom stale / Her infinite variety...."

"The credit of its execution is due to Monsieur Oscar Meunier, of Grenoble, who spent some days in doing the moulding. It is a bust in wax." (8)

Grenoble is a city in southeastern France, located at the foot of the French Alps. Holmes might have stayed closer to home to commission this work. One of the most famous London tourist attractions (still there today, and on-line at http://www.madame-tussauds.co.uk) was Madame Tussaud's Wax Museum. Tussaud learned the art of wax modeling in France, and became art tutor to the sister of King Louis XVI. Her art both damned and saved her: during the revolution, she was forced to use her skill to mold death masks of the guillotine's victims. Later, she inherited her teacher's collection of figures, and took them on tour in England until 1835, when she installed her waxworks in a building on Baker Street. In 1884, her grandson moved the collection to its present home on Marylebone Road, just around the corner from Baker Street.

"He is a harmless enough fellow, Parker by name, a garroter by trade, and a remarkable performer upon the Jew's harp." (8)

Garroting is a form of execution where the victim is strangled by a cord or wire twisted around his neck--not exactly a "harmless" trade. This sort of insouciant remark is typical of Holmes's dry sense of humor.

The "Jew's harp," also called the "jaw-harp" or "mouth-harp," is an ancient instrument used in many cultures. It consists of a small metal frame with a flexible prong in the middle. It is grasped in the teeth while the prong is plucked by the finger, taking advantage of the resonant chamber provided by the mouth. The instrument makes a one-note droning sound, complemented by varying overtones created when the shape of the mouth is changed. Its metallic, nasal sound is unmistakable.

An opera-hat was pushed to the back of his head, and an evening dress shirt-front gleamed out through his open overcoat. (10)

In other words, he has on a man's collapsible top hat and is wearing a tuxedo under his overcoat.

Then from the pocket of his overcoat he drew a bulky object, and he busied himself in some task which ended with a loud, sharp click, as if a spring or bolt had fallen into its place. Still kneeling upon the floor he bent forward and threw all his weight and strength upon some lever with the result that there came a long, whirling, grinding noise, ending once more in a powerful click. He straightened himself then, and I saw that what he held in his hand was a sort of gun, with a curiously misshapen butt. (10)

Pneumatic airguns were invented centuries ago. The airgun whose assembly is described here is powered, not by gunpowder, but by air stored in a bellows in the rifle's oddly shaped barrel. Detonation produces a sharp sound--softer than that of a conventional weapon, but still quite audible--but no flash or explosion. During Conan Doyle's time, airguns were used for sport and competitions were common. The odd noises Watson describes are the filling of the bellows with air, then the click of the breech lock after Moran loads the cartridges. Watson later hears the "strange, loud whiz" of the bellows emptying when the gun is fired.

It was a tremendously virile and yet sinister face which was turned towards us. With the brow of a philosopher above and the jaw of a sensualist below, the man must have started with great capacities for good or for evil. But one could not look upon his cruel blue eyes, with their drooping, cynical lids, or upon the fierce, aggressive nose and the threatening, deep-lined brow, without reading Nature's plainest danger-signals. (10)

Conan Doyle describes Colonel Moran's face in terms of 19th-century criminal anthropology, which was a combination of phrenology, misguided observations, and class prejudice. Criminologists of the time hoped to create a taxonomy of criminals--much as 19th-century biologists, botanists, paleontologists, etc., had classified the plant and animal kingdoms. Rather than basing their system on psychological or genetic traits (both these sciences were in their infancies), they relied upon physical measurements and characteristics as indicators of character and behavior. These systems failed, but were precursors of the more accurate science of criminology we have today. See last year's notes on The Hound of the Baskervilles.

"Ah, Colonel!" said Holmes, arranging his rumpled collar; "'journeys end in lovers' meetings' as the old play says." (10)

Holmes loosely paraphrases the Clown's song in Shakespeare's Twelfth Night (Act II, scene 3):

O mistress mine, where are you roaming?

O, stay and hear; your true love's coming,

That can sing both high and low:

Trip no further, pretty sweeting;

Journeys end in lovers meeting,

Every wise man's son doth know.

"I believe I am correct, Colonel, in saying that your bag of tigers still remains unrivalled?" (10)

As a member of the British colonial force in India, Moran, like other most other British officers at the time, hunted tigers for sport. This was not as risky as it sounds: Indian nobles and British officers sat on wooden platforms (or on the backs of elephants) and waited for native "beaters" to drive tigers out of the bush so that they could be shot at leisure. While waiting, the officers sat in luxury, drinking and eating delicacies. Still, the "bag," or number of tiger killed, was highly competitive. This blood sport began the tiger's decline towards extinction, which continues today. See Roshni Johar's article, "The scent of shikar," Sunday Tribune (India), April 6, 2003.

...with his savage eyes and bristling moustache he was wonderfully like a tiger himself. (10-11)

In Victorian criminology, the criminal was seen as a less-evolved human--a "throwback" to our animal ancestors.

"I wonder that my very simple stratagem could deceive so old a shikari," said Holmes. (11)

"Shikari" derives from the Anglo-Indian word "shikar," and denotes a big-game hunter in India. In the next paragraph, Conan Doyle has Holmes trace out a nice parallel between the colonel's capture and the use of a young goat as bait for a tiger. The colonel thought he was the hunter, but Holmes has cast him as the tiger, a role Moran does not especially like. The hunting metaphor begins earlier, as Watson and Holmes ride in the cab together. "I knew not what wild beast we were about to hunt down in the dark jungle of criminal London, but I was well assured from the bearing of this master huntsman that the adventure was a most grave one..." (7).

Holmes had picked up the powerful air-gun from the floor.... (11)

This gun, made especially for Professor Moriarty, is presumably the same gun Holmes fears in "The Final Problem," when he goes to Watson's home and asks the doctor to accompany him to the continent. In reality, air-guns are not completely silent.

"With your usual happy mixture of cunning and audacity, you have got him."

"Got him! Got who, Mr. Holmes?" (12)

As usual, Holmes manages to praise and ridicule Lestrade at the same time.

"...here is Morgan the poisoner, and Merridew of abominable memory, and Mathews, who knocked out my left canine in the waiting-room at Charing Cross...." (12)

All these criminals are imaginary, although Charing Cross is a real train station in London.

He handed over the book, and I read: "Moran, Sebastian, Colonel. Unemployed. Formerly 1st Bengalore Pioneers. Born London, 1840. Son of Sir Augustus Moran, C.B., once British Minister to Persia. Educated Eton and Oxford. Served in Jowaki Campaign, Afghan Campaign, Charasiab (despatches), Sherpur, and Cabul. Author of 'Heavy Game of the Western Himalayas,' 1881; 'Three Months in the Jungle,' 1884. Address: Conduit Street. Clubs: The Anglo-Indian, the Tankerville, the Bagatelle Card Club." (12-13)

Colonel Moran's resume is remarkably normal for his time and social standing. He came from a good family, attended the best schools, served honorably in India, and wrote two books. His military background, his interests in hunting and gambling, his club memberships–all make him seem more like an upstanding British gentleman than the right-hand man of a criminal mastermind like Moriarty.

"I have a theory that the individual represents in his development the whole procession of his ancestors, and that such a sudden turn to good or evil stands for some strong influence which came into the line of his pedigree. The person becomes, as it were, the epitome of the history of his own family." (13)

For Holmes, this theory is remarkably muddled and unscientific.

"...will embellish the Scotland Yard Museum...." (14)

Retention by the police of certain items belonging to prisoners was authorized by British law in 1869. In 1874, the storehouse of prisoners' property at Scotland Yard was opened to the public. Known as "The Black Museum" and, later, simply as "The Crime Museum," this museum holds, among other things, Jack the Ripper's notes, and death masks of hanged criminals. For a history of the museum and a partial list of its holdings, go to their website. Unfortunately, the museum is no longer open to the public, but is used as an educational resource by teachers of forensics and police work. Conan Doyle is listed as a visitor; however, Von Herder's air-gun does not figure among the exhibits.

|