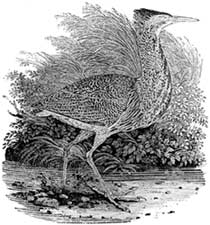

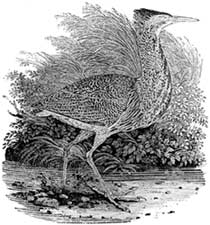

"Did you ever hear a bittern booming?"

The bittern is a marsh heron that almost became extinct in Conan Doyle's

time. Its weird "booming"—said to sound like air being blown over

the top of an empty bottle—has contributed to local legends. Its usual

habitat is reedy swamps, but it would not be expected to occur on

the moor.

A bittern, drawn by British naturalist

Thomas Bewick (1753-1828) for his two-volume work, A History of British Birds |

|

The

whole steep slope was covered with grey circular rings of stone,

a score of them at least.

"What are they? Sheep-pens?"

"No, they are the homes of our worthy ancestors.

Prehistoric man lived thickly on the moor, and as no one in particular

has lived there since, we find all his little arrangements exactly

as he left them. These are his wigwams with the roofs off. You can

even see his hearth and his couch if you have the curiosity to go

inside."

"But it is quite a town. When was it inhabited?"

"Neolithic man—no date."

Although Neolithic (and even earlier) humans did populate the moor,

the large concentration of visible stone ruins dates from the Bronze

Age (2,300 to 700 B.C.). Dartmoor has experienced roughly ten thousand

years of human habitation and use—with visible remains from at least

four thousand years. The land is dotted with burial mounds, cairns,

and religious monuments from several different eras—both ancient

stone circles and crude medieval stone crosses. The ruins of stone

huts remain, too, but are usually less complete than the ones Watson

describes in Hound. The moor has served as burial ground,

farmland, a place where mining and crude smelting was performed,

as foraging and grazing land, and, since 1951, as a national park.

Visit the Dartmoor National Park Authority's website for pictures

and more information about the 368 square-acre park: www.dartmoor-npa.gov.uk.

|