|

|

“The Adventure of the Musgrave Ritual” |

Notes l Bibliography l Download Issue 3

...and when I find a man who keeps his cigars in the coal-scuttle, his tobacco in the toe end of a Persian slipper, and his unanswered correspondence transfixed by a jack-knife into the very centre of his wooden mantelpiece, then I begin to give myself virtuous airs. (1)

Holmes's eccentric domestic arrangements have been imitated in faithful reproductions of the Baker Street rooms (e.g., the Sherlock Holmes Museum in Meiringen, Switzerland, and the Baker Street Museum in London), and in the name of at least one Sherlockian society: the Persian Slipper Club of San Francisco.

...with his hair-trigger and a hundred Boxer cartridges.... (1)

The name "Boxer" seems to apply to rifle, rather than pistol, cartridges. Conan Doyle is generally very lax with his designations for guns. Many commentators have disputed the ability of even a crack shot to place bullets in a perfect "V.R." without blowing all the plaster off the wall.

...with a patriotic V. R. done in bulletpocks.... (1)

With his marksmanship, Holmes is paying tribute to Queen Victoria: "Victoria Regina."

"Here's the record of the Tarleton murders, and the case of Vamberry, the wine merchant, and the adventure of the old Russian woman, and the singular affair of the aluminium crutch, as well as a full account of Ricoletti of the club foot and his abominable wife." (1)

These cases all have tantalizing names, but none has been written. Crutches in Conan Doyle's day would have been wooden, rather than aluminum ("aluminium" in British English).

"And here—ah, now! this really is something a little recherché." (1)

"Recherché " is French for "far-fetched," or "out of the ordinary."

"You may remember how the affair of the Gloria Scott, and my conversation with the unhappy man whose fate I told you of, first turned my attention in the direction of the profession which has become my life's work." (2)

"The Adventure of the Gloria Scott" was published in The Strand three months before "The Musgrave Ritual." It was a

reminiscence of

Holmes's first case, conducted while he was still at university.

"...at the time of the affair which you have commemorated in 'A Study in Scarlet'...." (2)

A Study in Scarlet, Conan Doyle's first Holmes and Watson novella, appeared in Beaton's Christmas Annual of 1887. Holmes did not catch the public imagination until his appearance in The Strand Magazine in 1891.

|

|

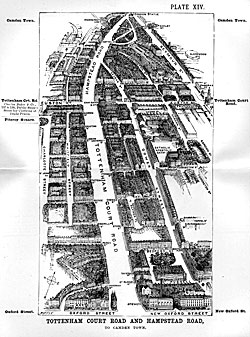

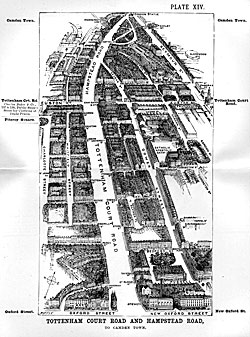

The British Museum and Montague Place can be seen at lower right. Montague Street is on the other side of the museum, off the right edge of the map. |

"When I first came up to London I had rooms in Montague Street, just round the corner from the British Museum...." (2)

Michael Harrison, in The London of Sherlock Holmes (Drake Publishers: New York, 1972), decides that Holmes lodged at 26 Montague Street, because his researches turned up an intriguing fact: in 1875, a certain Mrs. Holmes (Sherlock's mother?) leased the house next door at 24 Montague Street.

Founded in 1753, The British Museum is a vast storehouse of arts, culture, natural history, and science. Located in the area of London known as Bloomsbury, the British Museum welcomes over 5 million visitors a year from all over the world. Admission is free. See http://www.thebritishmuseum.ac.uk/ for more information about collections, history, and events.

"Reginald Musgrave had been in the same college as myself...." (3)

Whether Holmes attended Oxford or Cambridge—the two great British universities—has excited much disagreement among Sherlockians. Conan Doyle probably hoped to avoid controversy by never specifying one or the other.

"...though his branch was a cadet one...." (3)

That is, descended from a younger brother, not the line of eldest sons, who were traditionally inheritors of the main estate.

|

|

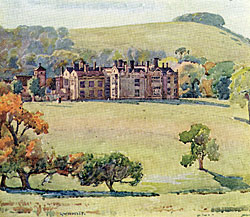

A watercolor of St. Mary's House, Bramber, from Viscountess Wolseley, Sussex in the Past (London & Boston: The Medici Society, 1928) |

|

A watercolor of Wiston Park, which, unfortunately, is not L-shaped like the Musgraves' home. From Viscountess Wolseley, Sussex in the Past |

"...which had separated from the Northern Musgraves some time in the sixteenth century, and had established itself in Western Sussex, where the manor house of Hurlstone is perhaps the oldest inhabited building in the county." (3)

Several models for Hurlstone have been suggested among the many ancient homes in West Sussex. Ads for St. Mary's House in Bramber, built in 1470 as an inn for Canterbury pilgrims, claim that its cellar inspired the story, but Conan Doyle seems to have had something grander in mind when he describes Hurlstone's "grey archways and mullioned windows and all the venerable wreckage of a feudal keep" (3). Two possible old West Sussex homes, culled from many, are Petworth House and Wiston Park. No mansion seems to have just the right combination of features to be a good match for Hurlstone: a ruined medieval castle attached to a more modern building in the shape of an "L."

"...grey archways and mullioned windows and all the venerable wreckage of a feudal keep." (3)

Mullioned windows have a solid divider through the center of the window. A feudal keep is a medieval castle.

"'...and as I am member for my district as well....'" (3)

In other words, Musgrave is a Member of Parliament, representing West Sussex.

"'I preserve, too, and in the pheasant months I usually have a house party....'" (4)

Musgrave maintains a game reserve on his estate grounds so that he and his invited friends can hunt the animals in season. For pheasant, the season lasts from October through January.

"'But this paragon has one fault. He is a bit of a Don Juan....'" (4)

A paragon is an example of perfection, while Don Juan is a

legendary

ladies' man.

"'...a cup of strong café noir ....'" (4)

French for "black coffee."

"'...and perhaps of some little importance to the archaeologist, like our own blazonings and charges....'" (5)

To "blazon" a coat of arms is to describe it in heraldic terms. "Charges" are objects placed on the field of the escutcheon, or the colored space of the coat of arms.

"'A fortnight—say at least a fortnight.'" (5)

A fortnight is two weeks—fourteen nights.

"'...to the edge of the mere....'" (6)

A mere is a small, marshy lake or pond.

"She was of Welsh blood, fiery and passionate." (6)

The fiery "Welsh temperament" is a longstanding stereotype that probably reflects old British attitudes towards the rebellious Welsh, who resisted British rule, with its imposition of the English language and the Church of England on their populace.

"'It is rather an absurd business, this Ritual of ours,' he answered, 'but it has at least the saving grace of antiquity to excuse it.'" (6)

For someone who finds the ritual absurd and trivial, Musgrave seems to feel quite ashamed of it. He keeps it under lock and key, reacts negatively when Holmes first asks to see it, and disparages it as "of no practical importance" and a "rigamarole."

"'Whose was it?

"'His who is gone.

"'Who shall have it ?

"'He who will come.

"'Where was the sun ?

"'Over the oak.'" (6)

In later editions, two more lines are interposed after "He who will come":

"What was the month?

"The sixth from the first."

In his 1935 play about the murder of Thomas Becket, Murder in the Cathedral, T.S. Eliot paraphrases the Musgrave Ritual.

"...all those generations of country squires...." (8)

Country squires are landowning gentry. Sherlock Holmes's own family was made up of country squires.

"'It was there at the Norman Conquest, in all probability,' he answered." (8)

The Normans, descendants of Scandinavian Vikings who had settled in France, conquered England in 1066 by winning the Battle of Hastings. William the Conqueror was their leader. Their conquest is immortalized in the Bayeux Tapestry.

|

|

A two-wheeled dog-cart pulled by two horses in tandem. From Hugh McCausland, The English Carriage (London: Batchworth Press, 1948) frontispiece. |

"We had driven up in a dog-cart...." (8)

The two-wheeled dog-cart was an all-purpose vehicle that could be modified to carry passengers—with or without baggage—or to drive out to shoot with a couple of dogs. It might be pulled by one horse, or, if the load was especially heavy, by two in tandem.

"Of course, the calculation now was a simple one. If a rod of 6ft. threw a shadow of 9ft., a tree of 64ft. would throw one of 96ft., and the line of the one would of course be the line of the other." (8)

Holmes solves a simple ratio to determine how long the shadow of the defunct elm would have been. 6:9 :: 64:x. Or, 6/9 = 64/x. x = 96.

"...having first taken the cardinal points by my pocket compass." (8)

The cardinal points are the four main directions.

"'There is a cellar under this, then?' I cried." (9)

When Musgrave earlier claimed to have searched the house "from cellar to garret" (6), he must have meant the new part of the house only. Otherwise, Brunson would have been found long before.

"...to which a thick shepherd's check muffler was attached." (9)

A muffler is a thick scarf.

"The attitude had drawn all the stagnant blood to the face, and no man could have recognised that distorted, liver-coloured countenance...." (9)

Brunson's face is suffering from livor mortis. After death, when the heart is no longer pumping blood, gravity causes the red blood cells to settle in the part of the body that is facing downwards, creating a purplish discoloration of the skin.

"You know my methods in such cases, Watson: I put myself in the man's place, and having first gauged his intelligence, I try to imagine how I should myself have proceeded under the same circumstances." (10)

Several times, Holmes speaks of the importance of empathic imagination in detective work. At other times, he seems to discount anything but logic and evidence. His method apparently combines both with the ability to change tactics to meet the needs of a particular case.

|

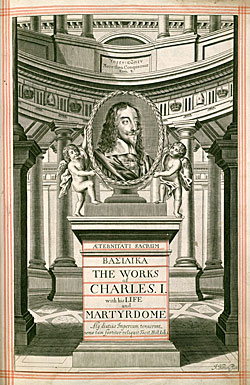

Charles I is portrayed here with three crowns: a heavenly crown of grace, marked "Gloria" (glory); a crown of thorns, marked "Gratia" (grace); and, lying on the ground, the actual crown of the Kings of England, marked "Vanitas" (vanity). Parliament was supposed to have destroyed the original crown, which was reconstructed after the Restoration.

|

|

The frontispiece of Stanford's copy of Eikon Basilike, The Pourtraicture of His Sacred Majestie in his Solitudes and Sufferings (No printer's name, 1648) elevates Charles I to the status of martyr. Note the crowns and bishop's miters lining the inside of the dome. |

"...so that it was unnecessary to make any allowance for the personal equation, as the astronomers have dubbed it." (10)

Nineteenth-century astronomers noticed that two observers, watching the sky from different points, would make slightly different measurements in space and time. They called this individual bias "the personal equation," despite the fact that it might have many disparate causes, such as possessing poor eyesight, making observations from different locations, or using less sensitive (or poorly calibrated) equipment. Holmes feels that Brunson is his equal in intelligence, and so makes no allowances for failures of logic, as he might with others.

"Or had some sudden blow from her hand dashed the support away and sent the slab crashing down into its place." (11)

Rachel Howells's declaration to Musgrave that she was "strong enough" (5) is now explained. Her hysterical laughter was provoked by the guilty recollection of what she had been strong enough to do.

"'These are coins of Charles I.,' said he...." (11)

The controversial reign of Charles I (1600-1649) ended with the English Civil War, which pitted the King against Parliament. Charles was beheaded for high treason, and Oliver Cromwell, General of the Parliamentary army, ruled for nine years as Lord Protector. After Cromwell's son ruled unsuccessfully, Parliament restored the monarchy in 1660 by investing Charles I's eldest son as Charles II.

During his imprisonment, Charles I was supposed to have written an elaborate self-justification: Eikon Basilike (Royal Portrait), The Pourtraicture of His Sacred Majestie in his Solitudes and Sufferings (1648). (This attribution of Charles's authorship was vouched for by the Royalists, but has been disputed by scholars.) The book came out a few days after Charles's execution, and encouraged people to see him as a Christian martyr. He was eventually canonized—the only one so honored by the Church of England.

"The metal-work was in the form of a double ring, but it had been bent and twisted out of its original shape." (11)

How the crown became twisted is a matter of speculation. Some commentators also wonder how the crown had turned black, since pure gold does not tarnish.

"'You must bear in mind,' said I, 'that the Royal party made head in England even after the death of the King....'" (11)

In other words, the Royalist party continued to attempt to preserve itself and to hide its relics for the future, even after the King was executed.

"'My ancestor, Sir Ralph Musgrave, was a prominent Cavalier, and the right-hand man of Charles II. in his wanderings,' said my friend." (11)

The wig-wearing Cavaliers were the Royalist party, while the rebellious Roundheads (Puritans) were named for their short, simple hairstyles.

"'There can I think be no doubt that this battered and shapeless diadem once encircled the brows of the Royal Stuarts.'" (11)

Holmes is saying that the crown is the 13th-century crown of Edward I. Parliament supposedly destroyed this crown after Charles I's execution.

"They have the crown down at Hurlstone—though they had some legal bother, and a considerable sum to pay before they were allowed to retain it." (11)

Even after paying a "considerable sum," why were the Musgraves allowed to keep the original crown of the kings of England? One would think that such a relic belonged in the Tower of London with the rest of the Crown Jewels.

From 1909 until 1930, when he died of heart failure at 71, Conan Doyle lived at Windlesham Manor (today a retirement home) in Crowborough, Sussex. An excellent golfer, he enjoyed living in a house that faced on the local golf course. That’s not the only thing the house had convenient access to.

In 1912, an amateur archaeologist named Charles Dawson made a startling announcement: he had found the “missing link,” humanoid skull bones of a species linking apes and humans, whose absence had bedeviled archaeologists since Darwin’s theory of evolution (in Origin of Species, 1859) had been widely accepted. The gravel pit in Piltdown where Dawson made his find lay practically on the golf course frequented by Conan Doyle, who often popped in to see how the dig was going.

Not everyone accepted Dawson’s discovery. The cranium seemed large, the brow ridge too small, compared with Neanderthal skulls found in France and Germany. In contrast, the broken jaw seemed too ape-like. Over the next several years, Dawson and others—notably the eminent archaeologist Sir Arthur Smith Woodward—discovered more fragments of the skull, as well as mammal bones and stone tools that seemed to prove the skull’s great age. Soon, a canine tooth was found. In 1915, a suspicious bone implement shaped like a cricket bat turned up, and, a few years later, pieces of a second skull.

Until 1953, when the fossils were exposed as fakes by a scientist named Kenneth Oakley, Piltdown Man was accepted by the general archaeological establishment as a genuine human ancestor. But who had constructed and planted the bogus fossils? Was it Charles Dawson, the discoverer; Martin Hinton, a British Museum scientist who enjoyed playing cruel jokes; or one of the other scientists or amateurs on the dig? Could it have been Arthur Conan Doyle, who lived seven miles away and often visited the discovery site in his motorcar?

To be continued in the next issue….

|