|

Notes l Bibliography l Download Issue 12

“His Last Bow” (1)

This is one of few stories in the Holmesian canon written in the third person; it was intended by Conan Doyle as an “epilogue” to Sherlock Holmes’s career. It was also meant to answer a question that blindsided the author while he was reviewing troops at the French front in 1916. Taken by surprise when asked if Holmes was serving in the English army, he answered, “He is too old to serve.” Apparently, Conan Doyle rethought that answer, and this story is the result.

—the most terrible August in the History of the world. (1)

“His Last Bow” was written in 1917, during World War I (1914-1918). After the June 1914 assassination of the Archduke Francis Ferdinand, and his wife Sophie, by Serbian nationalists, a series of diplomatic moves by Austria set off a chain-reaction of power-jockeying that resulted in mutual declarations of war by most of the great powers. In the first few days of August 1914, Germany invaded Belgium on its way to France, and Russia, Turkey, and England were dragged into war by their alliances. The war changed the face of Europe forever, resulting in the dismantling of the Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman Empires, the overthrow of ruling dynasties in Germany and Russia, and the redrawing of borders throughout the rest of Europe.

The war was widely greeted with nationalistic fervor; many believed that Europe had become stale and decadent, and that the war, which was predicted to last just a few months, would act as a needed purge. No one could have foreseen the terrible destruction and loss of life that would result. New technologies forever changed the way wars were conducted. Since the last major war in Europe—the Franco-Prussian War in 1870-71—the machine gun, rapid artillery, the submarine, chemical warfare, and other advances had made traditional warfare obsolete. The chivalric image of charging cavalry was replaced by the horrific reality of trench warfare, in which the same patch of ground could be fought over for months, and even years. The can-do idealism with which Conan Doyle (and Holmes, at the end of the story) greeted the war ended in disillusionment and grief. Conan Doyle lost his brother-in-law, two nephews, and his second child Kingsley, who died of pneumonia in October 1918 after being wounded on the Somme.

|

|

Harwich lies on the North Sea, at the mouth of the Stour and Orwell Rivers, north of the mouth of the River Thames. This map shows the area’s geology. From The Victoria History of the Counties of England: Essex, 2 vols. H. Arthur Doubleday and William Page, Eds. (Westminster: Archibald Constable: 1903) |

…at the foot of the great chalk cliff…. (1)

There are chalk cliffs in Sussex and Kent (e.g., the White Cliffs of Dover), but few chalk deposits in Essex, and none in northeastern Essex, where this story takes place. The white cliffs in Harwich are made up of limestone, calcite, and ancient volcanic ash, not chalk.

…the devoted agents of the Kaiser. (1)

“The Kaiser” was Wilhelm II, Emperor of Germany and King of Prussia from 1888 to 1918.

…of the Legation…. (1)

The “German Legation” is another term for its embassy.

…huge hundred-horse-power Benz car…. (1)

Karl Benz (1843-1929) invented the first practical automobile powered by an internal combustion engine. His car manufacturing company went through several incarnations, finally merging with Daimler in 1926 to manufacture the Mercedes-Benz car.

“They have, for example, their insular conventions, which simply must be observed.” (3)

Telling this story in the third person, not in the first person with Watson as narrator, gives Conan Doyle license to eavesdrop on the conversation of the two Germans, and to delineate their low opinion of the English. In the course of this conversation, Conan Doyle demonstrates his opinion that the Germans grossly underestimate the intelligence, pluck, and tenacity of the English, mistaking polite reserve and adherence to custom for placidity.

“…our good Chancellor is a little heavy-handed in these matters….” (3)

Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg (1856-1921) served as the German Chancellor from 1909 to 1917. His policies were generally liberal, and slanted toward negotiation rather than aggression, but he allowed those who favored war to dominate his foreign policy. A series of ham-handed diplomatic mistakes on his part did not serve the cause of peace. When Britain declared war on Germany over the German invasion of Belgium, whose neutrality was guaranteed by the 1839 Treaty of London, Bethmann Hollweg asked how Britain could go to war over “a scrap of paper.”

“…your four-in-hand takes the prize at Olympia.” (3)

A “four-in-hand” is a team of four matched horses, controlled by one driver, and meant for competition. Olympia is an exhibition hall in Hammersmith, London, formerly known as the National Agriculture Hall.

“…left yesterday for Flushing….” (3)

Flushing is an important harbor in Holland, across the North Sea from Harwich.

“Of course, it is just possible that we may not have to go. England may leave France to her fate. We are sure that there is no binding treaty between them.”

“And Belgium?” He stood listening intently for the answer.

“Yes, and Belgium too.” (3)

On August 3, 1914, Germany declared war against France. It sent troops into neutral Belgium on the night of August 3-4, 1914, demanding the right to cross Belgium on its way into France. England had no diplomatic commitment to defend France, but it was obliged by an 1839 treaty to defend Belgium. Accordingly, on August 4, Great Britain declared war against Germany. This story must take place in the first days of August, before it became clear what Germany would do, and how England would react.

“…especially when we have stirred her up such a devil's brew of Irish civil war, window-breaking furies….” (4)

The Germans supported the Irish rebellion with weapons and supplies, but they were unlikely to have aided the suffragists, referred to here as “furies,” or female personifications of vengeance from Greek mythology. Conan Doyle, who did not advocate voting rights for women, deplored the suffragists and all they stood for, especially when they began committing civil disobedience to draw attention to their cause.

|

|

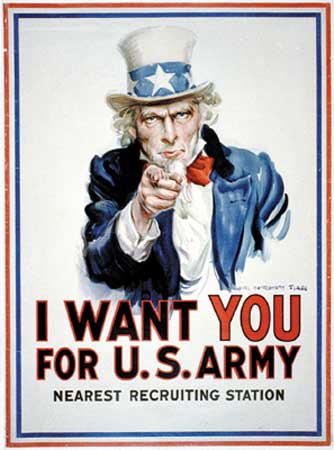

A World War I recruiting poster showing John Bull in much the same pose as American recruiting posters showed Uncle Sam. From the Wikipedia Commons |

“…with Mr. John Bull.” (4)

Created by John Arbuthnot in 1712, John Bull is a caricature representing both the English “everyman” and the country of England.

“But let us get away from speculation and back to real-politik.” (4)

“Real-politik” is practical, hand-on politics, as opposed to ideology. The word carries the pejorative connotation of using any means necessary to reach one’s goals.

…a long series of such titles as “Fords,” “Harbour-Defences,” “Aeroplanes,” “Ireland,” “Egypt,” “Portsmouth Forts,” “The Channel,” “Rosyth”…. (4)

An important naval base was located in Portsmouth, on the south coast of England. The Royal Naval Dockyard was at Rosyth, Scotland.

“…things are moving at present in Carlton House Terrace….” (4)

The German Embassy was located in Carlton House Terrace, Pall Mall. Today it is on Belgrave Square.

“…our most Pan-Germanic Junker….” (4)

The “Pan-Germanic” movement aimed at the unification of German-speaking peoples from all over Europe. The “Junkers” were German’s landed gentry, an elite group of rich, highly influential conservatives, supporters of the monarchy and the military, who would not be likely to look kindly on England.

“…and when you get that signal-book through the little door on the Duke of York's steps….” (4)

The “little door” is the door to the German Embassy, which used to lie near the York Column, where Regent Street meets The Mall.

“What! Tokay!” (4)

Imperial Tokay was a wine produced in small quantities under the Austro-Hungarian Empire. After the changes wrought by World War I, it was no longer made. It is sad and ironic that this rare wine, a symbol of old-world gentility, is used to drink a farewell toast to the world before the war—and to one of the greatest literary friendships—at the end of the story.

“Those are the lights of Harwich, I suppose,” said the secretary, pulling on his dust-coat. (5)

Harwich lies at the mouth of the Stour and Orwell Rivers, north of the mouth of the River Thames. It faces on the North Sea, but is not far from the English Channel and mainland Europe, making it of strategic importance. Regular ferry service to Europe from Harwich continues even today. Since the 17th century, a British Naval base has been located there. That Von Bork has chosen this spot above all others, right under the nose of the British Navy, is an irony that Conan Doyle surely intended.

“The heavens, too, may not be quite so peaceful, if all that the good Zeppelin promises us comes true.” (5)

In 1899, the German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (1838-1917) constructed an airship, called a “zeppelin,” based on another man’s design. Many thought that the zeppelin, a huge, rigid airship floated by gas cells and steered by means of a small engine with propellers, would dominate 20th-century aviation. The Germans used the zeppelin for long-range bombing raids and transportation, but it was superseded by the airplane before World War II.

“She might almost personify Britannia,” said he, “with her complete self-absorption and general air of comfortable somnolence.” (5)

Britannia, a female personification of Great Britain, is usually shown draped in classical robes, wearing a helmet and bearing implements of war. She resembles the goddess Athena, the French personification “Marianne,” Lady Liberty, and similar goddess figures. Changing the usual attitude of Britannia from vigilance to somnolence helps Conan Doyle drive home his point that the Germans thought that the English were complacent and unready for war.

“You can give me the glad hand to-night, mister,” he cried. “I'm bringin' home the bacon at last.” (5)

Conan Doyle’s love of American slang—and his stilted use of it—comes out here. The “glad hand” was not a “high five,” but was a hearty greeting that might include a handshake.

“Every last one of them—semaphore, lamp-code, Marconi….” (5)

“Semaphore” is a system of visual signals, usually by means of flags, although lights can also be used (as in “lamp-code”). Two ships, or ship and shore, must be within visual range to use semaphore. “Marconi,” or radio telegraphy, can be used to transmit Morse or other coded signals a good deal farther.

He was a tall, gaunt man of sixty, with clear-cut features and a small goatee beard, which gave him a general resemblance to the caricatures of Uncle Sam. (5)

Uncle Sam is a personification of the United States. Cartoonists in Punch, and American cartoonist Thomas Nast, developed the form in which he is usually represented today. (Judging from the illustration in The Strand, Altamont looks more like Abraham Lincoln.)

“Well, so was Jack James an American citizen, but he's doin’ time in Portland all the same.” (6)

“Jack James” is an imaginary spy doing time in a real jail that still exists today: Portland Prison in Dorset, England, located on an island in the English Channel.

“…in Portsmouth Jail….” (6)

Opened in 1878, Portsmouth Jail was located in Hampshire, a county in southern England.

“My landlady down Fratton way had some inquiries….” (6)

Fratton is a residential area in Portsmouth, Hampshire, on the south coast of England.

“It’s me for little Holland, and the sooner the better.” (6)

Holland remained neutral during World War I, so it made a safe refuge for traitors.

“No other line will be safe a week from now, when Von Tirpitz gets to work.” (6, 8)

An admiral in the German army, Alfred von Tirpitz (1849-1930) was responsible for building up the strength of the German navy in the years before World War I. He especially advocated submarine warfare.

“…from Franz Joseph's special cellar at the Schoenbrunn Palace.” (8)

Franz Joseph was the Austro-Hungarian Emperor (Austrian Emperor, 1848-1916; Hungarian King, 1867-1916) whose uncompromising stand toward Serbia after the assassination of Archduke Francis Ferdinand led to the outbreak of hostilities in World War I.

The Schoenbrunn Palace was the Hapburgs’ ornate summer palace in Vienna, built between 1690 and 1711.

“…sleeping stertorously….” (8)

He was snoring.

“But for your excellent driving, Watson, we should have been the very type of Europe under the Prussian juggernaut.” (8)

That is, they would have been crushed under the German/Prussian war machine. This line was removed in later editions.

“You can report to me to-morrow in London, Martha, at Claridge’s Hotel.” (8)

Located in London at the corner of Brook and Davies Streets, in the fashionable neighborhood of Mayfair, Claridge’s is just blocks from Park Lane and Hyde Park. It was founded in 1898, and is a London institution.

“…a German cruiser navigating the Solent according to the mine-field plans which I have furnished.” (9)

The Solent is a strait in the English Channel separating Hampshire from the Isle of Wight.

“When I say that I started my pilgrimage at Chicago, graduated in an Irish secret society at Buffalo, gave serious trouble to the constabulary at Skibbereen….” (9)

The “Irish secret society” could be Sinn Féin (“Ourselves Alone”), started in the mid-19th century to agitate for freedom from repressive British rule, and later associated with the Irish Republican Army. Since the potato famine of the 1840s, many Irish had immigrated to the United States, but had continued to collect money and plan for Home Rule.

Skibbereen is a town in the agricultural area near the southernmost tip of Ireland, in County Cork.

“How often have I heard it in days gone by! It was a favourite ditty of the late lamented Professor Moriarty. Colonel Sebastian Moran has also been known to warble it.” (9)

Professor Moriarty (Holmes’s nemesis), and his sidekick Colonel Sebastian Moran, appear, respectively, in “The Final Problem” (1893) and “The Empty House” (1903). Both characters also appear in the 1915 novel The Valley of Fear, which ran in The Strand just after “His Last Bow.”

“It was I who brought about the separation between Irene Adler and the late King of Bohemia when your cousin Heinrich was the Imperial Envoy.” (10)

This is a reference to the 1891 story “A Scandal in Bohemia.” Holmes, however, did not separate Irene Adler from the King of Bohemia; he tried, and failed, to recover from her a photograph of herself with the king. Irene Adler separated herself from the king and married another man.

“It was I also who saved from murder by the Nihilist Klopman, Count Von und Zu Grafenstein, who was your mother's elder brother.” (10)

The “Nihilist Klopman” and his would-be victim are made-up characters. The nihilist movement in Russia sought to destroy the reigning social order and its social inequities. Nihilists often used violent methods in their struggle for social and political reform.

“…you are a sportsman, and you will bear me no ill will when you realize that you, who have outwitted so many other people, have at last been outwitted yourself.” (11)

Holmes's extension of British sportsmanship to the spying game is surely a bit disingenuous.

“…see if even now you may not fill that place which he has reserved for you in the Ambassadorial suite.” (11)

Holmes is sarcastically suggesting that Von Bork go to the German embassy, where his failure to provide good information might not be greeted enthusiastically.

“But it’s God’s own wind none the less, and a cleaner, better, stronger land will lie in the sunshine when the storm has cleared.” (11)

Europe after World War I was certainly a different land, but perhaps not a sunnier one. By some estimates, 35 to 40 million people died.

|

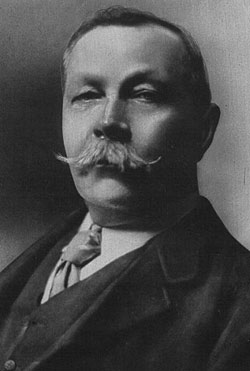

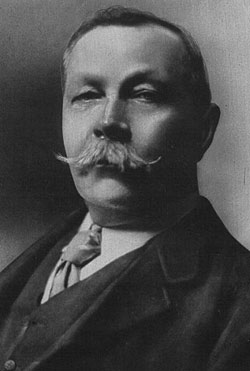

Conan Doyle in 1914, at the start of World War I. He was 55 years old. From Wikipedia Commons |

Arthur Conan Doyle gave up on Sherlock Holmes early, but never quite got free of him. Fearing that he would be “identified with what [he] regarded as a lower stratum of literary achievement,” he killed his hero, but eventually had to acknowledge that Holmes would remain a part of his life forever.

Today, Conan Doyle’s worst fears have been realized. While many of what he considered his “nobler” works are still in print, most people know his name because of Holmes and Watson. Conan Doyle’s influence on modern popular culture was greater than he could ever have imagined, not only through Holmes, but through the Professor Challenger novels, such as The Lost World. But most people today know nothing about the other side of Conan Doyle—the writer of historical fiction and heartfelt treatises on subjects he believed in; the crusader who fought for the rights of unjustly convicted prisoners, against colonial atrocities, for equitable divorce laws, and, most of all, for the recognition of spiritualism.

There is a whole world of Sherlock Holmes literature to be discovered, but there is also much to learn about Holmes’s creator. As fully-formed as he seems, Holmes is just one facet of the fertile imagination of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

|