Issue 9 : Hound, Chapters 12

| |

| This cover illustration is signed "A.G.J.," the (unknown) artist's initials | |

| |

| This cover from an Irish edition of Hound shows an animal that is more endearing than frightening | |

I stooped under the rude lintel, and

there he sat upon a stone outside, his grey eyes dancing with amusement

as they fell upon my astonished features.

Just as Holmes enjoyed trumping Watson's deductions about the walking

stick at the beginning of the story, now he revels in his friend's astonishment.

"…for when I see the stub of a cigarette marked Bradley,

Oxford Street, I know that my friend Watson is in the neighbourhood."

This imaginary tobacconist's shop would have been located just a few

blocks from Baker Street.

I was still rather raw over the deception which had been practised

upon me, but the warmth of Holmes's praise drove my anger from my mind.

Holmes often hurts Watson's feelings by withholding information from

him. Later, Holmes has a logical explanation for his deception, and

Watson always forgives him. For information about an interesting made-for-TV

version of Hound (2003) that explores this dynamic in depth,

see below.

When I learned that the missing man was devoted to entomology

the identification was complete.

It is ironic that Stapleton's one harmless passion leads to his downfall.

And a new sound mingled with it, a deep, muttered rumble, musical

and yet menacing, rising and falling like the low, constant murmur of

the sea.

Holmes and Watson hear the hound before they see it. The hound is an

elusive presence in the story—this authorial choice makes the

beast more frightening and formidable when it finally does appear.

Illustrators of Hound must decide what conception of the hound

will have maximum impact. Is it better to represent him as a monster,

or to leave him a shadowy presence? Filmmakers face the same dilemma.

Above right, the cover illustration for the first complete edition of

Hound shows the animal in silhouette against the moon. The

stylish, art-deco cover sports a red background with gold tracery and

questions marks. The interior illustrations by Sidney Paget had appeared

in the original Strand Magazine series. This edition was published

in England by Georges Newnes, owner of The Strand Magazine,

in 1902.

There could be no doubt about the beetling

forehead, the sunken animal eyes.

Again, Watson emphasizes Selden"s "beetling"—or Neanderthal—brow

and his "animal" eyes to show that he is a "born" criminal. Perhaps

this is one reason that Holmes and Watson neglect to take much trouble

over Selden"s corpse, while, if it had been Sir Henry"s body, they might

have considered carrying it to the hall.

"My difficulty is the more formidable of the two, for I think

that we shall very shortly get an explanation of yours, while mine may

remain for ever a mystery."

Holmes is right: Watson"s question is answered a few paragraphs later,

while Holmes"s own "difficulty" must wait until the end of the story

for its explanation.

"Sufficient for tomorrow is the evil thereof…."

Holmes paraphrases the King James New Testament: "Sufficient

unto the day is the evil thereof" (Matthew 6:34).

Hound on Film

Out of perhaps 250 films involving Holmes in

some capacity or other, The Hound of the Baskervilles has been

made into feature films at least 20 times since 1914, not counting the

many television versions. Each version has its own quirks; a few have

little or no relationship to the book. Multiple versions exist in English,

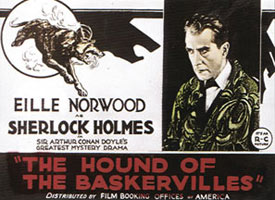

German, French, Italian, and Russian. British silent film actor Eille

Norwood, who has the distinction of having made more Holmes films than

anyone (47, in all), starred in a 1921 silent version of Hound.

His Holmes, forced to speak only through caption cards, was also slow-moving

and deliberate, because Norwood saw Holmes as a man who could not be

rattled. (Our modern Holmeses, such as Basil Rathbone and Jeremy Brett,

tend to be much more highly strung.) Norwood's films were set in post-World-War-I

England, not in Victorian times, as Conan Doyle would have preferred.

Aside from that small quibble, he enjoyed Norwood"s performances, and

once gave him a Holmesian dressing gown as a gift, which Norwood wore

in the films. Filmed on location in Dartmoor, the Norwood Hound

featured over-the-top acting, typical of the silent film era, plus a

hound whose jowls were—none too successfully—made to look

fiery with scratches on the film.

| ||

| Eille Norwood as Holmes, wearing the dressing gown given to him by Conan Doyle | ||

| ||

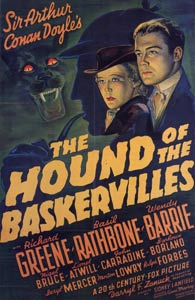

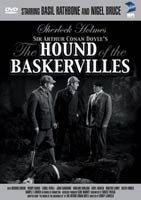

Basil

Rathbone did not get top billing in this version of Hound,

but was upstaged by a matinee idol named Richard Greene, little

remembered today |

||

| ||

Basil

Rathbone as Holmes and Nigel Bruce as Watson | ||

Basil Rathbone is considered by many to be the foremost interpreter of

Holmes. Visually, Nigel Bruce as Watson appears slightly too elderly,

but it is the buffoonish behavior written into the scripts that viewers

have criticized most. Fortunately, the rapport between Rathbone and Bruce

does not disappoint. Their first outing together as Holmes and Watson

was a 1939 version of Hound, and its success inspired 13 more films, several

only loosely based on the Conan Doyle canon.

The Rathbone-Bruce Hound

captures the original's feeling of the moor's spooky landscape,

even with studio sets. By necessity, the film plays fast and loose

with the plot, in order to squeeze a 15-chapter novel into a film

that is less than 90 minutes long. Its memorable last line of dialogue

refers rather strangely to Holmes's drug habit. As Holmes says a

hasty good-night and rushes from the room, he shouts, "Quick, Watson,

the needle!"

Jeremy Brett's and Edward Hardwicke's portrayals of Holmes and Watson

in Granada's 1988 production of Hound for British television

have become the favorites of many viewers. The plot remains largely

intact, although the pacing of events is, of necessity, somewhat

condensed. Brett's eccentric and neurotic, but appealing, portrayal

of Holmes is unique.

In a 2003 Masterpiece Theatre version shown on PBS, Richard Roxburgh

and Ian Hart give studied and emotional performances as Holmes and

Watson, while the hound itself, a computer-generated nightmare,

is perhaps less successful than the human element. This version

is distinguished by its emphasis on Holmes and Watson's friendship

in the context of the story. The plot is somewhat altered from the

original in order to focus on Holmes and Watson's difficult relationship.

The PBS Masterpiece Theatre web site contains extensive material

on both versions:

www.pbs.org/wgbh/masterpiece/hound.

Other Memorable Hounds

Der Hund von Baskerville. Dir. Carl Lamac. Perf. Bruno Güttner and Fritz Odemar. Ondra-Lamac, 1937. A series of silent films loosely based on The Hound of the Baskervilles was made in Germany from 1914-1921, and another in 1929. This 1937 "talking" film was, according to the "Internet Movie Database" (imdb.com), one of two movies found in Hitler's bunker at his death. The other was Der Mann, wer Sherlock Holmes war (The Man who was Sherlock Holmes; 1937), a story about two con men who impersonate Holmes and Watson. It is well known that Hitler loved movies, but we have no indication of why he seemed so fond of Sherlock Holmes.

The Hound of the Baskervilles. Dir. Terence Fisher. Perf. Peter Cushing and André Morell. Hammer Filmes, 1959. The first color version of Hound.

The Hound of the Baskervilles. Dir. Barry Crane. Perf. Stewart Granger and Bernard Fox. Universal for ABC-TV. 12 February 1972. A made-for-TV movie with William Shatner as Stapleton, this production received less-than-glowing reviews.

The Hound of the Baskervilles. Dir. Paul Morrissey. Perf. Peter Cook and Dudley Moore. Michael White, 1978. "A Grimpen Mire of comic enervation."—Financial Times "Truly one of the crummiest movies ever made."—Time Out

Priklyucheniya Sherloka Kholmsa i doktora Vatsona: Sobaka Baskerviley, (The Hound of the Baskervilles). Dir. Igor Maslennikov. Perf. Vasili Livanov and Yuri Veksler. Gostelradio/Lenfilm, 1981. One of a series of Sherlock Holmes mysteries filmed for Russian television from 1979 to 1986.

For more information, see:

Alan Barnes. Sherlock Holmes on Screen: A Complete Film and

TV History. Reynolds & Hearn: London, 2002.

The Internet Movie Database. www.imdb.com.

Visited February 27, 2006.

Scott Allen Nollen. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle at the Cinema.

McFarland: London, 1996.

PBS Masterpiece Theatre--The Hound of the Baskervilles.

www.pbs.org/wgbh/masterpiece/hound.

Visited February 20, 2006.