Sherlock Holmes, Victorian Gentleman

The heart of London in Doyle's time

|

A Bird's-Eye View of the

Thames |

In 1891, Sherlock Holmes was a character very much of his time and place, who appealed to British readers directly by confronting the messy, changeable world they lived in. Rather than dwelling in romance or in an idealized past, as many of Arthur Conan Doyle's other characters did, Holmes was grounded squarely in Victorian London. The Sherlock Holmes mystery stories, written over a forty-year span from 1887 to 1927, represented the good, the bad, and the ugly of Victorian society: its ideals, its accomplishments, and its deepest fears.

Arthur Conan Doyle's birth year, 1859, fell 22 years

into Queen Victoria's 64-year reign, a time of unparalleled growth and

optimism for the British Empire. Resources and labor taken from colonies

worldwide had made England prosper, and the time of serious independence

struggles lay in the distant future. Business flourished, technology blossomed,

and London grew at a great rate--from one million people to six in the

space of a century--creating problems of urban overcrowding familiar to

us today: poverty, homelessness, drug abuse, crime. While the great divide

between rich and poor and the economic and human strain of maintaining

the colonies exacerbated social problems that were as yet insoluble, Victorian

Britons, led by Victoria's husband Albert, put their faith in technology

and science. The contrasts and conundrums of this fascinating time provided

Conan Doyle with the raw material and the backdrop for Sherlock Holmes:

a man of science, undistracted by the gentler passions, who moved easily

through the disquieting urban space, using his wits to solve its moral

and practical dilemmas.

Physically, London could be a place of disturbing contrasts,

a cosmopolitan city where the middle class drank tea in comfortable drawing

rooms while epidemics of typhoid and cholera ravaged the squalid, overpopulated

East End. The putrid Thames River, the city's main source of drinking

water, despite the network of open sewers that dumped tons of waste into

it daily, carried a reeking cloud of contagion to all levels of society

as it meandered through the heart of the city.

Since 1844, the government had struggled with various solutions to the

sewage problem. In 1858, the year before Conan Doyle was born, the "Great

Stink," caused by the unfortunate effects of a hot summer on a sluggish,

polluted river, clotted with solid waste, drove thousands out of the city.

After years of effort, engineer Joseph Bazalgette designed and supervised

construction of a sewer system, completed in 1866, that drained sewage

away from the Thames and used the ebbing tide to wash it out to sea. London's

air was not much cleaner than its water. The burning of coal for heat

and cooking caused the greasy yellow "London fog" that Holmes and Watson

prowl about in:

In the third week of November, in the year 1895, a dense yellow fog settled down upon London. From the Monday to the Thursday I doubt whether it was ever possible from our windows in Baker Street to see the loom of the opposite houses.

—from "The Bruce Partington Plans"

|

Watson does not exaggerate;

in the worst London fogs, it was impossible to see past your nose |

Inhabitants of London had more

to fear from their city than an unhealthy environment. Barely thirty years

before Doyle's birth, London was a criminal's paradise. Whole areas of

the city were "owned" by criminal groups, and honest citizens hardly dared

to walk through certain neighborhoods at night, even armed. In 1829, the

Metropolitan Police was founded by Home Secretary Sir Robert Peel (hence

the nickname "Bobbies"). By Conan Doyle's birth in 1859, there were over

200 police constabulary units in England and Wales, under the jurisdiction

of individual counties. As Conan Doyle represents them in the Sherlock

Holmes stories, the constabularies were highly bureaucratized organizations

that did things "by the book"; constables themselves tended to be seen

as good-intentioned, but plodding, and not always successful. Luckily,

unlike Inspectors Lestrade and Hopkins, Holmes's erstwhile colleagues,

the Metropolitan Police was not actually forced to match wits with Holmes's

brilliant nemesis, Moriarty, leader of the most insidious criminal syndicate

in England.

In the Sherlock Holmes stories, at least, the idyllic-seeming English

countryside holds its own dangers. In Victorian England, small towns were

still structured on the feudal model that had prevailed for centuries.

In general, a large manor house, such as Baskerville Hall, dominated its

village. And although the village people no longer led their lives serving

the master of the manor, a strict social hierarchy still dictated that

the master was the community leader in more ways than one. The health

or dysfunction of the family living in the manor house could determine

the whole character of a village. Holmes and Watson pursue many mysteries

in the countryside surrounding London, where criminals carry on their

nefarious activities away from prying eyes. As Holmes remarks,

"It is my belief, Watson, founded upon my experience, that the lowest and vilest alleys in London do not present a more dreadful record of sin than does the smiling and beautiful countryside.… The pressure of public opinion can do in the town what the law cannot accomplish. There is no lane so vile that the scream of a tortured child, or the thud of a drunkard's blow, does not beget sympathy and indignation among the neighbours, and then the whole machinery of justice is ever so close that a word of complaint can set it going, and there is but a step between the crime and the dock. But look at these lonely houses, each in its own fields, filled for the most part with poor ignorant folk who know little of the law. Think of the deeds of hellish cruelty, the hidden wickedness which may go on, year in, year out, in such places, and none the wiser."

—from "The Adventure of the Copper Beeches"

England has seen a century of upheaval

since the first Sherlock Holmes stories burst upon the scene. The old,

mysterious London has melted away with its "pea-soup" fogs and plagues

of sewer gas; British colonies have gained their independence, one by

one; manor houses are as likely to be museums or bed and breakfast inns

as private residences. The problems faced by modern British society would

seem to have left the Victorian detective behind. Not so: the character

that Conan Doyle considered

unworthy of his serious literary aspirations still strikes a chord with

modern audiences. As the world changed around him, Sherlock Holmes, the

reassuring protector of British superiority, transcended his time, and

today is loved for his weaknesses and eccentricities as much as for his

strengths. In the 21st century, sequels and pastiches featuring

the quintessential detective are still being produced at a steady rate.

Arthur Conan Doyle's original readers recognized their city and their

time in the Sherlock Holmes stories. It was easy to imagine that he was

just around the corner, riding in the next hansom cab. No wonder so many

people believed that Holmes was real. Today, we can return to those stories

to immerse ourselves in the dank vapors and dark alleyways of London,

and glimpse another world in all of its splendor and squalor.

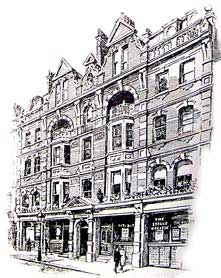

Arthur Conan Doyle and The Strand Magazine

|

The Strand Magazine's

offices on Southampton Street |

Popular literature, such as the Sherlock Holmes

stories, came of age along with another 19th-century innovation:

the popular magazine. Magazines had existed in some form since the 18th

century, but they had never been as cheap or as generally available. This

new medium demanded art forms that could be consumed in small bites: on

a train trip, or during a few leisure moments after a busy day. In earlier

times, literacy generally extended only as far as the middle class, but,

with the Education Act of 1870, elementary-school education became compulsory

across England. Changing labor laws had given workers more leisure time

and disposable income. Increased train travel, especially the advent of

daily commuting, triggered a demand for light reading material. Typesetting,

although still a complex and labor-intensive technology, had improved

to the point where printing houses could mass-produce high-quality material

that included photographs and engravings. Finally, the onerous Stamp Tax

had been reduced, making printed material more widely affordable.

|

|

|

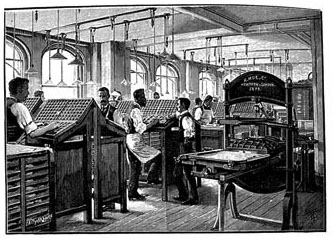

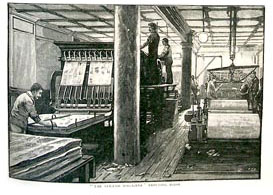

Strand Magazine typesetters at work |

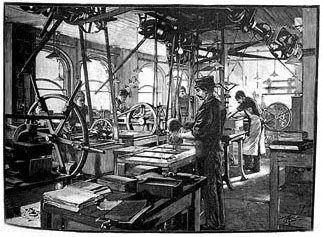

The Strand's electrotyping room |

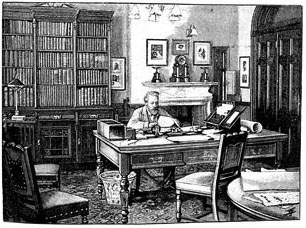

George Newnes, owner of The Strand |

Publishers quickly learned to target their publications

to the needs of particular segments of the population. Working-class people

with an elementary-school education read "penny weeklies" such as Tit-bits,

which contained short articles, bits of interesting information (what

we might call "sound-bites"), and serialized stories. For the middle class,

especially those with intellectual aspirations, magazines provided more

in-depth articles on politics, science, history, economics, and the arts,

as well as fiction that appealed to slightly more developed tastes than

what appeared in Tit-bits.

A "bird's-eye view" of

the Strand (1892) |

Founded in January 1891, The

Strand Magazine, named after a fashionable London street, was aimed

squarely at its target audience's middle-class tastes. A

typical issue might feature illustrated articles of scientific and historical

interest, a series of humorous cartoons on a theme, pictures of famous

people at different ages (from toddler to adult), interviews with celebrities,

a treatment of a controversial issue of the day, and one or more pieces

of fiction. The factual articles were not too complex, and the fiction

tended to feature a mystery or "twist" to keep the reader interested.

Nevertheless, the articles were skillfully edited and stylishly presented

in a sophisticated format. Whoever bought a copy of The Strand

felt like a true Londoner.

|

A cover of The

Strand Magazine from 1907 |

Conan Doyle wanted fame and success as a writer, and he went about achieving it more systematically and shrewdly than he had approached his medical career. First, he hired a literary agent, A. P. Watt, the very first man to advertise that sort of service. Then, he thought long and hard about what might appeal to his audience. Fearing that serialized stories would be of limited use to a reader who missed an issue, Conan Doyle decided to write stories that could be read independently but whose central character would be the same. Sherlock Holmes, who had already been the hero of Conan Doyle's novels A Study in Scarlet and Sign of the Four, seemed like a good candidate for such a series. Conan Doyle's agent submitted "A Scandal in Bohemia" to The Strand. It was accepted, and Conan Doyle was contracted to write a total of six stories featuring his detective.

|

The Strand's printing

room |

Because of the very small success achieved by his first two Holmes novels, Conan Doyle's expectations were low. When "A Scandal in Bohemia" appeared in July 1891, during The Strand Magazine's first year, it was an instant hit. In assuring his own future, Conan Doyle also assured the grand success of The Strand, which ran monthly until 1950.