Through

the years, Lombroso tried to modify his theory to go beyond biology

by taking account of environmental, social, and psychological factors;

however, his work remained flawed by his preconceptions of what

criminality meant. He defined criminals as people who were already

in jail, and never compared them to the general population in order

to test his theory. His writings had a great influence on the American

criminal justice system, but today are no longer taken seriously,

except as a historical curiosity. Towards the end of his life, Lombroso—like

Conan Doyle—became an ardent spiritualist.

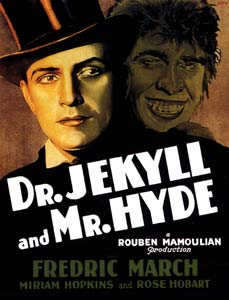

The idea that criminals possess a low forehead and other "primitive" physical characteristics was influenced heavily by phrenology and anthropometry. Such ideas also surfaced in the literature of the time.

I caught one glimpse of his short,

squat, strongly-built figure as he sprang to his feet and turned

to run. At the same moment by a lucky chance the moon broke through

the clouds. We rushed over the brow of the hill, and there was our

man running with great speed down the other side, springing over

the stones in his way with the activity of a mountain goat. |

||||