|

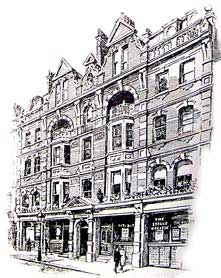

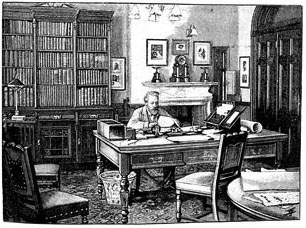

The Strand Magazine's offices

on Southampton Street |

Popular literature, such as the Sherlock Holmes stories, came of

age along with another 19th-century innovation: the popular

magazine. Magazines had existed in some form since the 18th

century, but they had never been as cheap or as generally available.

This new medium demanded art forms that could be consumed in small

bites: on a train trip, or during a few leisure moments after a

busy day. In earlier times, literacy generally extended only as

far as the middle class, but, with the Education Act of 1870, elementary-school

education became compulsory across England. Changing labor laws

had given workers more leisure time and disposable income. Increased

train travel, especially the advent of daily commuting, triggered

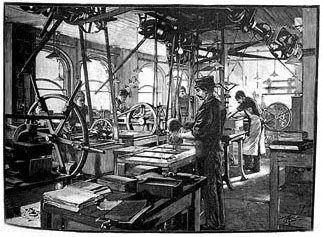

a demand for light reading material. Typesetting, although still

a complex and labor-intensive technology, had improved to the point

where printing houses could mass-produce high-quality material that

included photographs and engravings. Finally, the onerous Stamp

Tax had been reduced, making printed material more widely affordable.

|

|

|

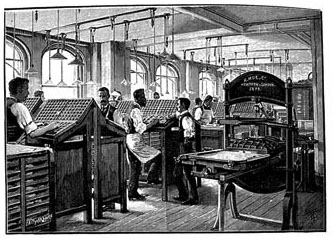

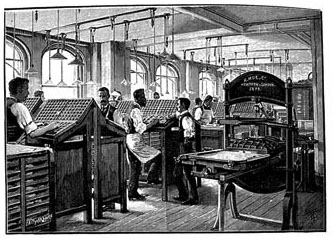

Strand Magazine typesetters at work |

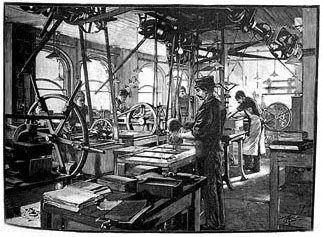

The Strand's electrotyping

room |

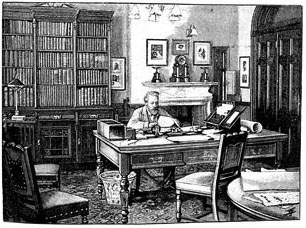

George Newnes, owner of The Strand

and Tit-bits |

Publishers quickly learned to target their

publications to the needs of particular segments of the population.

Working-class people with an elementary-school education read "penny

weeklies" such as Tit-bits, which contained short articles,

bits of interesting information (what we might call "sound-bites"),

and serialized stories. For the middle class, especially those with

intellectual aspirations, magazines provided more in-depth articles

on politics, science, history, economics, and the arts, as well

as fiction that appealed to slightly more developed tastes than

what appeared in Tit-bits. |