|

Notes l Bibliography l Download Issue 6

|

|

“The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton” |

"The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton" (1)

This is a post-hiatus story (written after Holmes's return), but since Watson gives no date, it could have taken place any time during Holmes's career.

...I saw a stately carriage and pair, the brilliant lamps gleaming on the glossy haunches of the noble chestnuts. (2)

A "carriage and pair" is a private coach with a matched pair of horses, a symbol of the immense riches that Milverton has been able to accumulate from his dirty trade.

...in a shaggy astrachan overcoat.... (2)

His "astrachan overcoat" (usually spelled "astrakhan") is another sign of Milverton's overstated opulence—a coat made of lambskin with the curly wool still attached. The King of Bohemia wore a similar coat in "A Scandal in Bohemia." Conan Doyle uses astrakhan as an indicator of poor taste; a true gentleman would probably not wear such a thing.

|

|

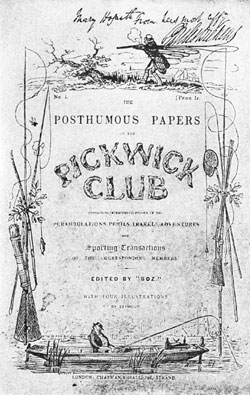

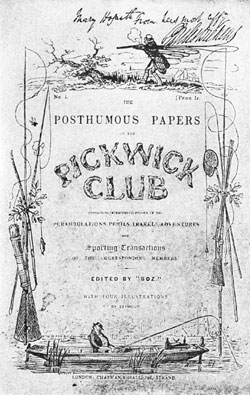

The original 1837 cover, autographed by Dickens. From the Wikipedia Commons |

There was something of Mr. Pickwick's benevolence in his appearance.... (2)

Mr. Pickwick is the protagonist of Charles Dickens's picaresque novel, The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, more commonly known as The Pickwick Papers, a novel consisting of a loosely related series of adventures experienced by the kindly Mr. Pickwick and his friends. The novel was originally issued in serial form between April 1836 and November 1837. Pickwick is usually portrayed as round-cheeked, bespeckled, and somewhat portly—the very picture of a harmless man.

"...by turning her diamonds into paste." (3)

In other words, by selling her diamonds and replacing them with fakes made of "paste" (glass).

"...a paragraph in the Morning Post ...." (3)

A conservative London newspaper published from 1803 to 1937, the Morning Post was first known for its unique coverage of high culture, including literature, music, and the arts. In the 1920s its decline was hastened by a series of anti-Semitic articles.

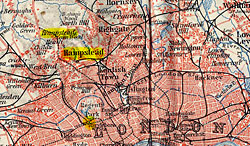

"...it is a long drive to Hampstead...." (4)

It is approximately three miles north from 221B Baker Street to Hampstead, and slightly farther to Hampstead Heath, mostly uphill.

"But the girl, Holmes?" (4)

Watson worries about the young woman's feelings, while Holmes cavalierly assumes that she will turn her affections smoothly from him to his rival. As usual, the case, not emotion, is paramount for Holmes.

"Since it is morally justifiable I have only to consider the question of personal risk. Surely a gentleman should not lay much stress upon this when a lady is in most desperate need of his help?" (5)

Perhaps Holmes is showing his class bias here. A simple serving girl's feelings are expendable, but a lady must be spared. Or, is Holmes simply appealing to Watson's chivalric nature as the most effective way of convincing him that the burglary must be done?

"This is a first-class, up-to-date burgling kit, with nickel-plated jemmy, diamond-tipped glass-cutter, adaptable keys, and every modern improvement which the march of civilization demands. Here, too, is my dark lantern." (5)

A "jemmy" is a crowbar, and a dark lantern is a lantern with an adjustable cover that directs a small beam of light only where the user wishes it to fall.

|

|

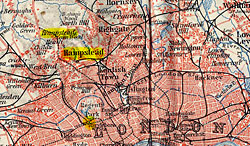

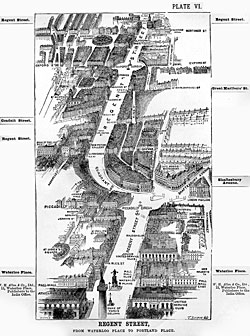

Baker Street lies just south of Regents Park, in the center of the map; Hampstead village and Hampstead Heath can be seen just to the north. Greater London lies to the east. From Karl Baedeker, London and Its Environs (1911) |

"...we shall drive as far as Church Row." (5)

Church Row is an actual street in Hampstead, several blocks south of Hampstead Heath. The 1911 Baedeker guide describes it as "picturesque."

In Oxford Street we picked up a hansom and drove to an address in Hampstead. Here we paid off our cab, and with our great-coats buttoned up, for it was bitterly cold and the wind seemed to blow through us, we walked along the edge of the Heath. (5)

Once a sleepy village, Hampstead had become part of metropolitan London by Conan Doyle's time. The village and the heath lie on a high plain, northwest of central London, about 440 feet above sea level. Hampstead Heath is a vast tract of wild, open land (791 acres), in contrast to the manicured parks found in the rest of London. Parts of the land belonged to an estate, while the rest was the Hampstead village common. Consumptives (including the poet John Keats) were drawn to live in the area because of its altitude and fresh, cool air.

"...he is a plethoric sleeper." (6)

"Plethoric" implies that Milverton is red-faced from overindulgence in food and drink, and that he snores.

...two of the most truculent figures in London.... (6)

Watson is convinced that he and Holmes look dangerous.

The place was locked, but Holmes removed a circle of glass and turned the key from the inside. (6)

Holmes's technique of using a diamond cutter to remove a circle of glass still turns up in movies and television shows today.

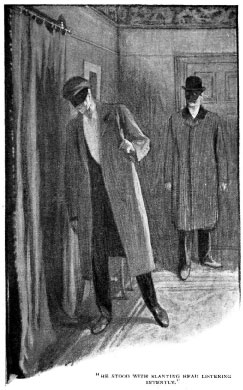

We were in Milverton's study, and a portière at the farther side showed the entrance to his bedroom. (6)

A "portière" is a heavy curtain hung across a doorway to stop drafts from blowing under and around the sides of the door.

...with a marble bust of Athene on the top. (6)

Athene is the Greek goddess of wisdom and weaving. Her presence in Milverton's study implies that the man is wily and dangerous to underestimate.

The high object of our mission, the consciousness that it was unselfish and chivalrous, the villainous character of our opponent, all added to the sporting interest of the adventure. (6)

Holmes and Watson speak of their mission to retrieve the letters both in terms of a chivalric quest to save a fair lady, and as a kind of "sport," or contest between themselves and Milverton. The chivalric part of the quest is selfless, but the sporting contest is quite personal—a vendetta between Holmes and Milverton, in which Holmes is determined to prevail, even at the risk of his reputation. Several times in the Holmesian canon, someone remarks that Holmes would have made a dauntingly successful criminal, had he not turned his talents to serving the law. This adventure is the test of that theory.

...the dragon which held in its maw the reputations of many fair ladies. (7)

It is clear that Watson sees the burglary as a knight's quest, but casting the safe as a dragon to be slain is a bit fanciful of him.

|

|

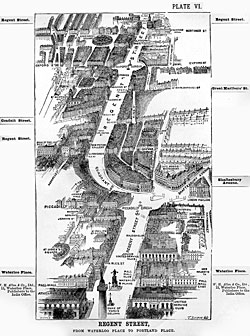

Oxford Street comes in from the left, leading to Oxford Circus at center. Note Piccadilly Circus and gentlemen's clubs toward the bottom of the map.

From Herbert Fry, London Illustrated by Twenty Bird's-Eye Views of the Principal Streets (London, 1892) |

He wore a semi-military smoking jacket, claret-coloured, with a black velvet collar. (8)

Here is yet another sign of Milverton's high life. He treats himself well, and does not skimp on transportation, food and drink, or clothing.

I understood the whole argument of that firm, restraining grip—that it was no affair of ours; that justice had overtaken a villain; that we had our own duties and our own objects which were not to be lost sight of. (9)

Many times in the canon, Holmes takes the law into his own hands when he thinks justice would be better served by him than the authorities. He sees the limitations of the law—its bureaucracy, its inflexibility—and he considers himself a superior arbiter of morality. His conviction that he is superior to the laws of the land is part of the dark, dangerous side of Holmes that could so easily slide into megalomania. Writers of later Holmes stories have enjoyed plumbing these depths of his character.

...and one fellow raised a view-halloa as we emerged from the veranda.... (9)

A "view-halloa" once signified the cry of a fox-hunter who had spotted the prey, but later came to mean any cry of sighting or alarm.

...a glass-strewn coping. (10)

A "coping" is the top of a masonry wall, and might be set at a slant to make the wall more difficult to scale. In this case, it also has jagged bits of glass embedded in it that serve the same function as barbed wire today.

He hurried at his top speed down Baker Street and along Oxford Street, until we had almost reached Regent Circus. (11)

Regent Circus, at the intersection of Regent and Oxford Streets, is more commonly known as Oxford Circus (see map at right).

|

|

The first meeting of Sherlock Holmes (Gillette) and Alice Faulkner. From The Strand Magazine, December 1901 |

William Gillette’s conventionally handsome face might seem too beefy, too well-endowed with chin, and even too healthy for some readers’ vision of Holmes, but theatre audiences happily accepted him. Harder for some to stomach—including Conan Doyle, who resisted the idea at first—was the inevitable love interest that Gillette inserted into his melodramatic revision of Conan Doyle’s play Sherlock Holmes. Instead of going back to Irene Adler from “A Scandal in Bohemia,” Gillette created an original character for the role, Miss Alice Faulkner. “But Mr. Holmes,” she says, “I…I want to ask you something. Don’t you care for me at all?” After an interminable scene in which their love is deemed to be impossible, it suddenly becomes not only possible, but a brilliant idea. “Your powers of observation are somewhat remarkable, Miss Faulkner,” says Holmes, “and your deduction is quite correct! I suppose—indeed I know—that I love you.”

Although Gillette’s face represented the standard Holmes for many years, his capitulation to romance for the detective did not catch on. Conan Doyle continued to portray Holmes’s attitude towards women as he always had: polite, even chivalrous, but with enough scorn to suggest some deep, interesting psychology that has kept writers of “further adventures” busy for years.

For further exploration, a search of “YouTube” under “William Gillette” yields a slide show of pictures against a recorded excerpt from Gillette’s play, spoken by the actor when he was 82, including part of the love scene.

|